Treasure Hunting

Steely Artistry

From the "Fairfield County Times"

Written by Richard Stevenson (August, 2001)

Photographed by London Shearer Allen

In the peripatetic Winnebago Nation of wanderers called the United States

of America, John R. Hansen, Jr. has chosen to stay put in Southport. By

the time he was a teenager he knew what he wanted to do with his life,

and he went ahead and did it. Mr. Hansen, called jay by everyone except

importunate telemarketers, is a founding partner of Hansen & Hansen,

the Southport gun dealers who've been in business since 1972.

Like his father, grandfather and great-grandfather, Jay Hansen grew up in Southport,

in a venerable house on the Old Post Road that has since, regretfully,

been sold out of the family. As a Connecticut kid he was surrounded by

history, and he is descended from Simeon North, who made the first U.S.

Model flintlock pistol in 1799 - a design North appropriated from our

Revolutionary War allies, the French. Jay's uncle and grandfather worked

at the Remington Arms factory, and his father took him to see some Revolutionary

War muskets when he was about 10. At Christmas of that year, intuiting

the boy's interest, his father gave Jay a period musket. After that, young

Mr. Hansen was well and truly hooked, first as a collector, then as a

dealer.

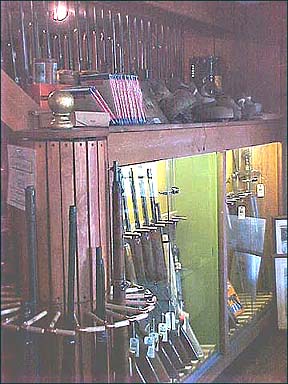

When

he was 30, Mr. Hansen opened for business in a former slaughterhouse at

244 Old Post Road, which is still the firm's headquarters. Hansen &

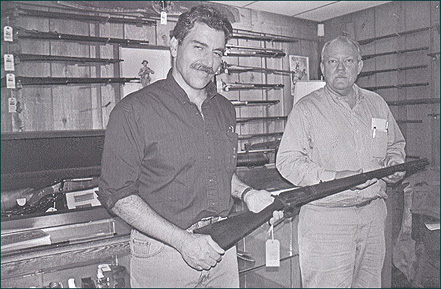

Hansen currently sells 3,000 to 4,000 firearms a year. Mr. Hansen’s partner

in the firm is Tom LoPiano, a longtime friend and collector who joined

the business in 1998. The partners are both appraisers as well as dealers;

the firm offers gunsmithing on the premises, and jay Hansen has headed

up several of the gun field's professional organizations. Although Hansen

& Hansen sells modern firearms and ammunition, plus gun-related paraphernalia

of all sorts, Mr. Hansen and Mr. LoPiano are happiest when they are dealing

in antique pieces.

When

he was 30, Mr. Hansen opened for business in a former slaughterhouse at

244 Old Post Road, which is still the firm's headquarters. Hansen &

Hansen currently sells 3,000 to 4,000 firearms a year. Mr. Hansen’s partner

in the firm is Tom LoPiano, a longtime friend and collector who joined

the business in 1998. The partners are both appraisers as well as dealers;

the firm offers gunsmithing on the premises, and jay Hansen has headed

up several of the gun field's professional organizations. Although Hansen

& Hansen sells modern firearms and ammunition, plus gun-related paraphernalia

of all sorts, Mr. Hansen and Mr. LoPiano are happiest when they are dealing

in antique pieces.

A recent cover of Man at Arms, a magazine devoted to the collecting of guns

and swords, shows a rare and costly antique revolver of the sort Hansen

& Hansen likes to buy and sell. The magazine says the object is "a

deluxe cased presentation Transition Colt Baby Dragoon, #11665, with an

extra 4-inch barrel," and adds: "This revolver is believed to be the only

known Baby Dragoon that is deluxe factory engraved with two barrels."

Mr. Hansen recalls that his firm sold the piece for around $200,000.

The firm currently has several rarities of particular antiquarian interest

for sale. If you'd like to own a pair of Colt revolvers in custom casing

that belonged to a Union colonel who died in battle, bring about $100,000.

For a very reasonable $2,000 you can take home an antique Winchester Model

1886 lever-action rifle. An "extremely rare" Colt Model 1847 Whitneyville

Walker percussion revolver, which comes with a picture of the Confederate

militia general who was its original owner, is priced at $250,000. For

more information the number to call is 259-5424.

A $250,000 price for a fine and rare antique Colt will not surprise anyone

who watches the world of antiques in general. Prices for the best material

across all categories have spiked skyward in recent years. A single Windsor

armchair made nearly $140,000 at a recent Greenwich auction. The other

day a rare decorated shaving mug - yes, a shaving mug - was hammered down

at $42,550 at a Washington, D.C. auction. And nowadays multi-million-dollar

price tags for the best pieces of American furniture are commonplace.

Connecticut has long been a center of gun manufacturing, and of course the best-known

name in the field is Colt, short for Colonel Samuel Colt of Hartford.

William Hosley, former furniture curator in the Wadsworth Atheneum and

now executive director of the Antiquarian & Landmarks Society, wrote

a fine book about Sam and Elizabeth Colt, including much valuable material

on the Colt manufacturing activities in Paterson, N.J., and Hartford.

"There is nothing that cannot be produced by machinery,"

said Colt in 1854, with his showman's flair and the period's complete faith in technology.

Mark Twain visited the Colt establishment in 1868, when the colonel's

empire was in full swing, and wrote: "The Colt's revolver manufactory

is a Hartford institution...a dense wilderness of strange iron machines.

One can stumble over a bar of iron as he goes in at one end, and find

it transformed into a burnished, symmetrical, deadly "navy" (revolver)

as he passes out at the other. It must have required more brains to invent

all these things than would serve to stock 50 Senates like ours."

"God created men; Colonel Colt made them equal" runs the old frontier saying.

Antique arms authority and writer Norm Flayderman opines that in the field

of antique arms collecting there is no name more illustrious than that

of Colt. In the hearts of many it is synonymous with the American revolver.

Beginning in 1837 the name Colt has a proud and distinct association with

virtually every event in American history in which weapons were used and

carried.

Scholars who study American decorative arts have long noted

that everything is related, literally and figuratively. The people who made furniture

in any given area were all cousins and in-laws. So were silversmiths, blacksmiths,

whitesmiths and gunsmiths - and weavers, potters, clockmakers, decorative

painters and carvers and gilders. They cribbed decorative and design ideas

from each other and took ideas with them when they moved from town to

town, which was very common.

Scholars who study American decorative arts have long noted

that everything is related, literally and figuratively. The people who made furniture

in any given area were all cousins and in-laws. So were silversmiths, blacksmiths,

whitesmiths and gunsmiths - and weavers, potters, clockmakers, decorative

painters and carvers and gilders. They cribbed decorative and design ideas

from each other and took ideas with them when they moved from town to

town, which was very common.

One of the most intriguing cases of migrating motifs is this: 18th

century rococo designs, incorporated into the fanciest, high-style Philadelphia

furniture, also made their way into the vocabularies of early Pennsylvania

gunsmiths, makers of famous "Kentucky" rifles, Joe Kindig, Jr, influential

York, Pa, antiquary, historian, antique dealer and inveterate collector

of Kentucky rifles, wrote a pioneering book, "Thoughts on the Kentucky

Rifle in the Golden Age." In it he says:

"The gunsmiths who produced the Kentucky rifle were, I believe, the finest

artisans in eighteenth century Americana. The Kentucky rifle maker has

to be a master working in at least three materials - wood, iron and brass.

He had to be skilled in the forging (or at lest the rifling and finishing)

of iron barrels and the making and carving of wooden stocks, and in the

designing and engraving of brass and silver mounts."

"The gunsmith who could forge and temper a flintlock

that would repeatedly strike a good spark was equal in skill to the finest

workers in iron. Kentuckys were almost always stocked in curly maple,

one of the hardest woods to work with, and often ornamented with carving

equal to that found on our finest Chippendale furniture. In the designing

and engraving of the patch boxes and silver inlays, and in the casting

of butt plates and trigger guards, the gunsmith’s skill often equaled

that of the silversmith. And so, as three artisans in one, the Kentucky

rifle maker produced a purely American work of art, a thing of beauty

without a European prototype."

These works of art were also deadly accurate weapons. And they were accurate

at almost three times the range of the muskets carried by most armies

of the times. As the Kindig book points out, if America had used the Kentucky

rifle more widely, the Revolution would probably have been shorter. At

the Battle of Saratoga, a private soldier named Murphy killed an English

general named Frazier with one shot from his Kentucky rifle. Frazier's

death appears to have been the turning point in the battle, leading to

General Burgoyne's surrender of the entire British force. Encouraged by

that victory, the French decided to help the Americans. And so a single

shot from a Kentucky rifle helped secure America's independence.

These works of art were also deadly accurate weapons. And they were accurate

at almost three times the range of the muskets carried by most armies

of the times. As the Kindig book points out, if America had used the Kentucky

rifle more widely, the Revolution would probably have been shorter. At

the Battle of Saratoga, a private soldier named Murphy killed an English

general named Frazier with one shot from his Kentucky rifle. Frazier's

death appears to have been the turning point in the battle, leading to

General Burgoyne's surrender of the entire British force. Encouraged by

that victory, the French decided to help the Americans. And so a single

shot from a Kentucky rifle helped secure America's independence.

In the War of 1812, Andrew Jackson's army of 5,000 included 2,000 frontiersmen

carrying Kentucky rifles - who had come down the Mississippi in flatboats

to help at the Battle of New Orleans. Jackson knew the men, their weapon

and how to use both. The British took a terrible licking, sailing away,

having sustained more than 2,000 casualties, including their commanding

general. The Americans had eight killed and 13 wounded for a total of

21 casualties. Now that's a definitive victory.

A pleasant day-trip to the Litchfield Historical Society will reward the

gun collector/historian who's never made the journey before. The society

owns and displays several long guns made by Medad Hills, an 18th

-century gunsmith from Goshen. Hills, who lived from 1729 to 1808, made

some of the best long guns, called fowlers or fowling pieces, during the

1750's and 60's, the years of the French & Indian wars. During the

Revolution he supplied muskets to the fledgling American forces, and in

1779, at age 50, he saw action with the 17th Connecticut regiment.

His gravestone survives in Goshen's Cemetery located on east Street, North.

One of the most intriguing characteristics of long guns and pistols made

by Hills is how completely and clearly they are marked. Medad Hills marked

all his guns with engraved silver plates and escutcheons. A fowling piece

at the Litchfield Historical Society tells us the gun was finished on

August the 26th, 1758.

It is inscribed to the Reverend Mr. Silvenus Osborn, first minister of the

Congregational Church in nearby warren, who presumably shot for the pot

when he's finished his weekly sermon to the faithful.